PART TWO OF A TWO-PART SERIES

By Margaret Bobonich, DNP, FNP-C, DCNP, FAANP; Douglas DiRuggiero, DMSc, MHS, PA-C; and Mark Hyde, PhD, PA-C

Abstract

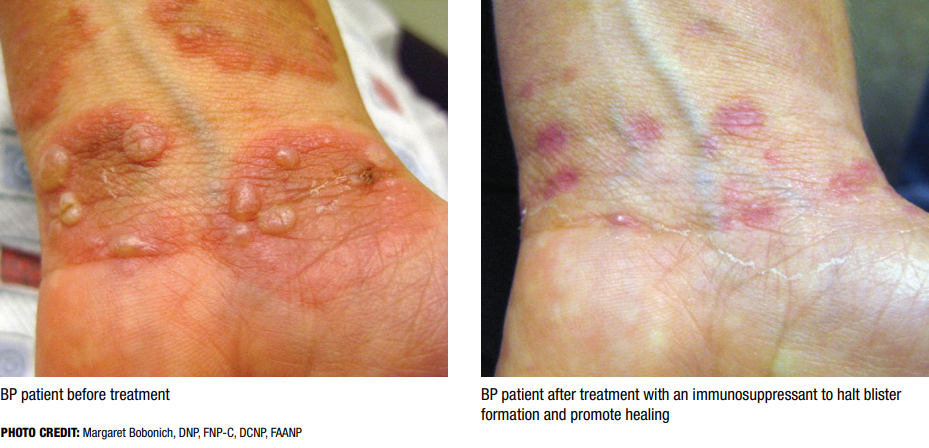

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an inflammatory skin disease that commonly presents as vesicles/bullae on the skin and sometimes involves mucous membranes. Part One of this series highlighted the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnostic considerations of BP. Here, we review diagnostic criteria for bullous pemphigoid, baseline and ongoing monitoring, and pharmacotherapies. A focus on chronic disease management includes topical and systemic corticosteroids, steroid-sparing agents, and new targeted drug therapies to reduce the risk of toxicities and adverse effects including dupilumab (Dupixent, Sanofi & Regeneron), which was recently U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for adult patients with BP.

- Introduction

- Diagnostic Criteria

- Baseline Assessment and Periodic Monitoring

- Therapeutic Approach to BP

- Skin Care

- Pharmacotherapy

- Systemic Therapies

- Systemic Therapies, Non-Immunosuppressant

- Non-FDA Approved, Non-Conventional Emerging Therapies

- Conclusion

Introduction

BP requires a strategic management approach based on an accurate diagnosis, a stratified treatment plan, timely initiation of therapies, and careful attention to skin care. Since BP can persist for months to years, long-term monitoring of the patient’s disease activity is critical. It is also important to consider potential complications, and the risk of adverse events associated with drug therapy is critical in BP patients. Therapeutic options for treatment of BP may be limited by comorbid conditions associated with BP, such as diabetes, neurological disorders, cardiovascular disease, renal insufficiency, and venous thromboembolism, particularly in elderly patients.1,2 Since polypharmacy is much more common in the elderly, as is BP, drug-to-drug interactions must also be weighed when initiating and maintaining pharmaceutical treatments.

Diagnostic Criteria

Early recognition of BP symptoms is crucial, as the varied clinical presentations can challenge even the most experienced clinician’s ability to make a prompt diagnosis. The patient’s symptoms, clinical assessment, and medical and drug history are major features that contribute to the diagnostic criteria for BP. Since BP can initially present in the elderly as persistent or intermittent pruritus without primary skin lesions, clinicians should include BP in the differential diagnosis for patients aged 60 and older who present with chronic pruritus.

Early recognition of BP symptoms is crucial, as the varied clinical presentations can challenge even the most experienced clinician’s ability to make a prompt diagnosis. The patient’s symptoms, clinical assessment, and medical and drug history are major features that contribute to the diagnostic criteria for BP. Since BP can initially present in the elderly as persistent or intermittent pruritus without primary skin lesions, clinicians should include BP in the differential diagnosis for patients aged 60 and older who present with chronic pruritus.

When there is a high index of suspicion for bullous or non-bullous pemphigoid, clinicians should consider immunohistochemical tests to confirm the diagnosis. The 2022 Updated European S2K Guidelines for the Management of Bullous Pemphigoid initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) outlines diagnostic criteria for BP.3 In addition to classic cases of BP, this task force provides recommendations for patients with non-bullous lesions along with guidance when direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing is negative in patients suspected with BP (Figure 1).

Baseline Assessment and Periodic Monitoring

Disease Severity

The Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) provides a reliable and objective tool for measuring disease activity and monitoring therapeutic response.4 A subjective measure of pruritus is evaluated on a separate visual analog scale (VAS).

- SKIN ACTIVITY SCORE (0–120): Includes blisters/erosions and urticarial/eczematous lesions across body regions.

- MUCOSAL INVOLVEMENT (0–12): Though rare in classic BP, mucosal scoring is relevant in atypical or severe cases.

- SUBJECTIVE PRURITUS SCORE (0–30): Based on a 10-point VAS over the past 24 hours, seven days, and one month.

Cumulative scores from the BPDAI are fundamental for categorizing disease severity as mild, moderate, and severe.5

Serum ELISA BP180

In addition to aiding in the diagnosis of BP, a serum ELISA for anti-BP180 may correlate to disease activity in some patients. Testing for reactivity may help gauge a patient’s response to therapy but also aid in predicting the risk for relapse before discontinuing therapy.6

Quality of Life

In addition to the BPDAI, clinicians should assess the impact of BP on a patient’s quality of life as lesions can cause severe pain, pruritus, and impair function. Questionnaires such as the Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI) can identify and document important physical, psychological, and social variables to consider in the plan of care.

History and Physical Examination

Collaboration with the patient’s primary care provider is imperative for a baseline assessment with careful attention to the presence or risk for comorbidities such as neurologic and psychological conditions, metabolic disease, and cardiovascular events.7 Since BP can last for months to years, often relapsing, the importance of ongoing health assessments cannot be overstated. Both the disease state and therapeutic interventions can make the management of BP challenging due to age-related comorbidities in the elderly.

A comprehensive medical history and review of systems should be performed along with a detailed drug history. Knowing that BP can be drug-induced, clinicians should pay careful attention to any new medications within six months prior to lesion onset or symptoms. However, clinicians should consider exploring this risk beyond one year as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (gliptins) and immune checkpoint inhibitors have been noted to cause a delayed onset of BP.8 A complete physical examination should be performed at baseline and periodically. Age-appropriate health screenings and additional testing, based on risk assessment and review of systems, can aid in the early detection of disease.

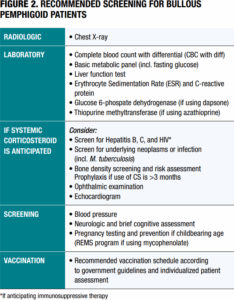

Laboratory and Diagnostic Prescreening

Baseline and periodic screening for BP patients can detect sequelae from disease as well as potential complications from drug therapy (Figure 2).3 Although general recommendations for testing and vaccinations are identified in the EADV guidelines,3 it’s important to anticipate individualized risks and complications for every patient.

Baseline and periodic screening for BP patients can detect sequelae from disease as well as potential complications from drug therapy (Figure 2).3 Although general recommendations for testing and vaccinations are identified in the EADV guidelines,3 it’s important to anticipate individualized risks and complications for every patient.

Therapeutic Approach to BP

BP is a complex and chronic blistering disease requiring an individualized management approach. Patients with mucous membrane involvement may have a greater disease burden and make control of the disease more difficult. Overall goals for BP management include:

- Decrease blister formation

- Decrease pruritus

- Promote skin barrier repair from blisters/erosions

- Reduce adverse effects from drug therapy for disease control

- Recognize comorbidities early

Skin Care

The skin barrier is disrupted in BP, which may cause pain,

pruritus, impaired function, and an increased risk of complications. Therefore, good skin care is the cornerstone of

supportive management in BP. This includes:

- CLEANSING. Patients should cleanse daily with gentle care using non-soap cleansers.

- MOISTURIZATION. Use emollients that promote barrier repair, reduce transepidermal water loss, and reduce itching.

- AVOIDANCE OF TRAUMA. Avoid mechanical trauma, such as friction or pressure.

- WOUND CARE. Use non-adherent dressings over blisters or erosions to promote healing and reduce infection

- MONITORING FOR INFECTION. Promote patient education for early recognition of infection.

- ADDRESSING PRURITUS. Utilize topicals such as anti-itch or corticosteroids for intact skin. Oral H1 antihistamines may be prescribed, but they can cause sedation, so use them with great caution in the elderly.

Pharmacotherapy

Guidelines for management of BP include a therapeutic approach based on disease severity, relapse, and responsiveness

to drug therapy.3

Treatment regimens should be individualized, with periodic re-evaluation for disease control, adverse

effects, and steroid-sparing opportunities.

- MILD BPDAI (<20) TO MODERATE BPDAI (≥20 AND <57) LOCALIZED BP

- Topical corticosteroids – usually high-potency

- MODERATE-TO-SEVERE BPDAI (≥57 BP)

- Doxycycline – favorable safety profile for the elderly

- Systemic corticosteroids – the standard but prompt transition to steroid-sparing agents

- Coventional immunosuppressants—such as azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate—reduce risks with long-term use of corticosteroids

- WHEN BP IS DEPENDENT ON CORTICOSTEROID THERAPY OR RELAPSING

- May consider adjunct therapy with steroid-sparing immunosuppressants

- If the patient is in poor health or conventional immunosuppressants are contraindicated, consider doxycycline, dapsone, or omalizumab

- REFRACTORY OR SEVERE CASES BP RESIDENT TO ORAL PREDNISONE

- Consider conventional immunosuppressants or in combination with prednisone

- Consider other therapeutic options including rituximab, dupilumab*, omalizumab, intravenous immunoglobulins, and immunoabsorption

*Dupilumab is the only FDA-approved drug for BP

Systemic Therapies

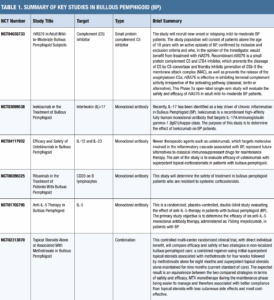

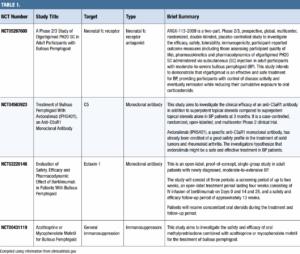

Many excellent references can oer information and guidance on initial, maintenance, combination, and emerging therapies for BP. Unless otherwise noted, the following information was gleaned from the authors’ collective clinical experience, Werth, et al.’s narrative review of therapies (2024),9 and Karakioulaki, et al.’s comprehensive pipeline review (2024).10

Corticosteroids

While considered the cornerstone of therapy, a guiding principle in BP management is to limit and manage a patient’s exposure to systemic glucocorticoids. Quantity and application frequency of topical corticosteroids should also be monitored as they have been shown to contribute not only to cutaneous adverse events (atrophy, striae, dyschromia, infection) but also to known systemic corticosteroid side effects (Cushingoid syndrome, metabolic changes, hypertension, osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture, and glaucoma).11,12 Corticosteroid-sparing adjuvant agents should be initiated early in the treatment paradigm to accelerate disease control and facilitate a more rapid and shorter course of oral corticosteroids. Furthermore, utilize these drugs if existing comorbidities contraindicate the use of oral corticosteroids, and select them based on insurance coverage, contraindications, and past treatment failures.

Conventional Immunosuppressants

Conventional, synthetic adjunctive therapies can be immunosuppressive but still be safer than long-term systemic corticosteroids. These therapies can vary in efficacy, safety, and monitoring requirements. When added to a topical and oral corticosteroid treatment regimen, these therapies can decrease steroid dependence and sometimes be effective as a monotherapy (once the disease is stable).

Methotrexate (MTX)

Prolonged, low-dose treatment with MTX is well-established as an effective mono- and adjunctive therapy in BP. The drug carries a category X pregnancy rating. CBC, kidney, and liver monitoring is required every two weeks for six weeks, monthly for three months, then every three months. MTX can deplete folate levels, so folate supplementation is required. Cumulative dose on liver function must be monitored, and methotrexate-induced pneumonitis is a rare adverse event.

Azathioprine

Weight-based dosing of azathioprine with slow titration can be an effective therapy for BP. Clinicians should monitor CBC, renal, and liver function weekly for the first four weeks, then every three months. Checking an initial TPMT (thiopurine methyltransferase) and NUDT15 level can help predict azathioprine metabolism. Those with low TPMT activity may need a reduced dose to avoid significant bone marrow suppression. Check the amylase level if the patient has abdominal pain and/or persistent nausea and vomiting, as acute pancreatitis is a rare serious side effect.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)

All prescribers of MMF and females of reproductive potential should participate in a mycophenolate REMS program due to fetal harm risk. MMF also may increase risk of infection and malignancy. This agent’s increased SE profile make it a second- or third-line agent to others in this category.

|

|

Systemic Therapies, Non-Immunosuppressant

These traditional non-immunosuppressants can be effective, affordable, and safe combination therapies with tapering oral steroids. They include:

Doxycycline

Doxycycline is a tetracycline antibiotic. It is cost-effective. Patients should be cautioned about photosensitivity. While well-tolerated, doxycycline may affect GI systems in elderly BP patients. BP patients may need eight to 16 weeks of doxycycline therapy.

Dapsone

Dapsone is a sulfone antibiotic originally utilized to treat leprosy. It is affordable, but requires baseline CBC, liver function tests, and Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD). Patients on dapsone must be monitored closely for signs of hemolysis or methemoglobinemia via lab work weekly for four to six weeks, and then monthly for six months. Avoid dapsone during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Note that glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) tests can be inaccurate and unreliable while on dapsone, rarely (with long-term, high-dose use), hand or foot muscle weakness and renal papillary necrosis can occur. Dapsone is particularly helpful for those with IgA involvement on direct immunofluorescence.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) works by reducing pathogenic antibodies. It is a good option for treatment-refractory cases and for those where antibiotic avoidance and stabilization of the immune system is important. IVIG is highly effective with rapid resolution (two to three weeks), and well-tolerated, but it requires IV infusion and can be expensive and burdensome to get insurance coverage. Watch closely for hemolytic anemia, and monitor liver and kidney function for BP patients on IVIG. Baseline IgG level can help establish a trough IgG level.

Dupilumab

Dupilumab inhibits the signaling of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13), key drivers of type 2 inflammation, which is implicated in the pathogenesis of BP.

The FDA approval of dupilumab in BP was based on results from the pivotal ADEPT Phase 2/3 study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of dupilumab compared to placebo in adults with moderate-to-severe BP. Patients were randomized to receive dupilumab 300mg (n=53) or placebo (n=53) added to standard-of-care oral corticosteroids (OCS). During treatment, all patients underwent a protocol-defined OCS-tapering regimen if control of disease activity was maintained. During the FDA review, the analyses were updated. The FDA-approved results at 36 weeks in the label for dupilumab compared to placebo are:

- 18.3% of patients experienced sustained disease remission compared to 6.1% (12.2% difference; 95% confidence interval: -0.8% to 26.1%), the primary endpoint

- 38.3% of patients achieved clinically meaningful itch reduction compared to 10.5%

- Median cumulative OCS dose was 2.8 grams compared to 4.1 grams

In this elderly population, the most common adverse events (≥2%) more frequently observed in patients on dupilumab compared to placebo were arthralgia, conjunctivitis, blurred vision, herpes viral infections, and keratitis. Additionally, one case of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis was reported in one patient treated with dupilumab and zero patients treated with placebo.13

Non-FDA Approved, Non-Conventional Emerging Therapies

Omalizumab

Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to IgE and prevents IgE binding to FcεR1. Multiple case reports and a two-case series (six and 11 patients) of patients with severe BP who experience significant improvement in itch and blister counts, well tolerated and minimal side effects. Average of four to five months’ treatment duration to obtain significant improvement and can have high recurrence rates.9

Rituximab

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to B cell surface protein CD20. A case series (seven patients) demonstrated a decrease in steroid use while halting the formation of new lesions in all patients at six months. This group reported no serious adverse events, but other retrospective and case studies have reported serious adverse events including infectious pneumonia, varicella-zoster virus sepsis with pulmonary and meningeal involvement, and hypogammaglobulinemia.9

Janus Kinase Inhibitors (JAKi)

While there are no randomized controlled trials, case reports of JAKi obtaining clearance, reducing flares, and maintaining remission have been published: upadacitinib (Rinvoq, AbbVie) (15mg daily allowed 20-day gradual reduction of prednisolone leading to complete remission in eight weeks and no flares after five months of follow-up),14 baricitinib (Olumiant, Eli Lilly) (4mg daily produced complete remission of psoriasis and BP in 24 weeks),15 tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Pfizer) (significant improvement in concurrent psoriasis and BP).16

Conclusion

Bullous pemphigoid has a complex pathophysiology that involves multiple autoimmune and autoinflammatory pathways. Whether broadly impacting the immune system with oral corticosteroids and/or traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, or specifically targeting T cells, B cells, eosinophils, and interleukin (IL)-5, complement factors, chemokines, intracellular receptor kinases, or neonatal Fc receptors (FcRn), randomized, controlled trials assessing the efficacy and safety of these medications are needed. The recent FDA approval of dupilumab for BP is an exciting step in our efforts to offer safe alternatives that reduce itch, lesion severity, and ultimately reduce (or eventually eliminate) oral corticosteroid dependence in patients suffering from this disease. The therapeutic pipeline is promising and bright.

REFERENCES

- Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger J. The association between bullous pemphigoid and neurological disorders: a systematic review. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27(5):472–481. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28681724/

- Cugno M, Marzano AV, Bucciarelli P, et al. Increased risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with bullous pemphigoid. The INVENTEP (INcidence of VENous ThromboEmbolism in bullous Pemphigoid) study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(1):193–199. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26245987/

- Borradori L, Van Beek N, Feliciani C, et al. Updated S2 K guidelines for the management of bullous pemphigoid initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(10):1689–1704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35766904/

- Murrell DF, Daniel BS, Joly P, et al. Definitions and outcome measures for bullous pemphigoid: recommendations by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):479–485. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22056920/ http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.032

- Masmoudi W, Vaillant M, Vassileva S, et al. International validation of the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index severity score and calculation of cut-off values for defining mild, moderate and severe types of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(6):1106–1112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33067805/

- Bernard P, Reguiai Z, Tancrède-Bohin E, et al. Risk factors for relapse in patients with bullous pemphigoid in clinical remission: A multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(5):537–542. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19451497/

- Huttelmaier J, Benoit S, Goebeler M. Comorbidity in bullous pemphigoid: up-date and clinical implications. Front Immunol. 2023 Jun 29;14:1196999. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37457698/

- Tasanen K, Varpuluoma O, Nishie W. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor-associated bullous pemphigoid. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1238. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31275298/

- Werth VP, Murrell DF, Joly P, et al. Pathophysiology of bullous pemphigoid: Role of type 2 inflammation and emerging treatment strategies (narrative review). Adv Ther. 2024;41(12)4418–4432. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39425892/

- Karakioulaki M, Eyerich K, Patsatsi A. Advancements in bullous pemphigoid treatment: A comprehensive pipeline update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25(2):195–212. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38157140/

- Egeberg A, Schwarz P, Harsløf T, et al. Association of potent and very potent topical corticosteroids and the risk of osteoporosis and major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(3):275–282. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33471030/

- Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Schwartz RA, Cork MJ. Adverse effects of topical glucocorticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):1-15; quiz 16-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16384751/

- Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with bullous pemphigoid: Results from LIBERTY-BP ADEPT phase 2/3 study. Late breaking research session 2. Presented at: 2025 American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 8, 2025; Orlando, Florida.

- Nash D, Kirchhof MG. Bullous pemphigoid treated with Janus kinase inhibitor upadacitinib. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;32:81–83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36691588/

- Xiao Y, Xiang H, Li W. Concurrent bullous pemphigoid and plaque psoriasis successfully treated with Janus kinase inhibitor Baricitinib. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(10): e15754. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35920701/

- Li H, Wang H, Qiao G, et al. Concurrent bullous pemphigoid and psoriasis vulgaris successfully treated with Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib: a case report and review of the literature. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;122:110591. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37441809/

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Margaret Bobonich, DNP, FNP-C, DCNP, FAANP, is a Nurse Practitioner and the Founder of Center for Dermatology NPs and PAs. She is also the founding Co-Editor-in-Chief of JDNPPA.

Douglas Diruggiero, DMSC, MHS, PA-C, is a Certified Physician Assistant at the Skin Cancer & Cosmetic Dermatology Centers in Rome, GA. He is also the Founding Co-Editor-in-Chief of JDNPPA.

Mark Hyde, PHD, PA-C, is an Assistant Professor and Physician Assistant at the University of Utah Dermatology in Salt Lake City, UT.

DISCLOSURES

Margaret Bobonich is on the Advisory Boards of Lilly USA, Bristol Myers Squibb, Organon (Dermavant), and Janssen. She is a Consultant for Lilly USA, Organon (Dermavant), and Bristol Myers Squibb.

Douglas DiRuggiero is a speaker and/or advisory board member for Amgen, AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Organon, Galderma, Incyte, Lilly, Novartis, SanofiRegeneron, Takeda, and UCB.

Mark Hyde has served on an advisory board for Leo Pharma.