By Veronica Richardson, ANP-BC, DCNP, and Rachel Woods, FNP-BC, DCNP

- Introduction

- Patient Impact and Experience

- Types of Diffuse Hair Loss

- FPHL

- TE

- Diffuse AA and Alopecia Areata Incognita

- The Initial Hair Loss Appointment

- History of Present Illness

- Clinical Exam

- Workup and Diagnostic Testing

- Conclusion

Introduction

Hair loss is a common dermatologic concern affecting both men and women. As clinicians, we understand that there are many different types of alopecia. Alopecia can be scarring, non-scarring, patchy, or diffuse. In the United States, approximately 50 million men and 30 million women have androgenetic alopecia, the most common type of diffuse hair loss.1 The global hair loss supplement and treatment market size as of 2024 was estimated at $8.04 billion.2 By 2030, this figure is estimated to be more than $11 billion.2 It is suggested that the frequency of patients presenting to dermatology for hair- and scalp-related disorders is increasing significantly;3 yet many clinicians report a knowledge gap when it comes to evaluating patients with hair loss. In fact, 56% of responders from a recent Dermatology Nurse Practitioner (NP) and Physician Assistant (PA) certification exam review course evaluation survey requested additional education on hair and nails. This article aims to assist the clinician in developing an efficient approach to the evaluation and diagnosis of the female patient presenting with diffuse hair loss.

Patient Impact and Experience

Both men and women seek consultation for their hair loss. However, the impact of hair loss on quality of life (QoL) is more significant in women.4 Women with hair loss reported lower self-esteem, higher social anxiety, and less life satisfaction compared to their male counterparts.5 Women are more likely to seek dermatology consultation and spend their financial resources on products to conceal their hair loss.6

The psychological impact of female pattern hair loss (FPHL) has been measured using a variety of validated tools such as the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 (HSS29), Skindex-16, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI).7-8 Using the Global Skindex-29, patients with FPHL had worse scores compared to patients with vitiligo, and near-equivalent scores of patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.7 These findings put the degree to which hair loss negatively impacts our female patients into sharp focus.

Research has shown that there is a lack of correlation between the severity of hair loss and the impact it has on the QoL of female patients,9 and patients may perceive their hair loss as being more severe than the clinician does. The significant impact on QoL and perceived severity lead many patients to seek consultation, yet the consultation experience can vary greatly. Some patients are willing and able to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket for a visit with an expert that lasts several hours. Others may wait months to see a dermatologist and leave having felt rushed or unheard.10 Pressure to see more patients, less time allocated for each patient visit, limited training on hair loss disorders, and patient desires to address multiple dermatologic concerns during one visit impede the ability of providers to thoroughly evaluate patients complaining of hair loss.

Types of Diffuse Hair Loss

The hair loss disorders that most commonly present with diffuse hair loss include androgenetic alopecia or female pattern hair loss (FPHL), telogen effluvium (TE), diffuse alopecia areata (DAA), and alopecia areata incognita (AAI). These will be discussed in this article. Anagen effluvium, another form of diffuse hair loss most commonly caused by exposure to chemotherapeutic agents, will not be addressed in this article.

FPHL

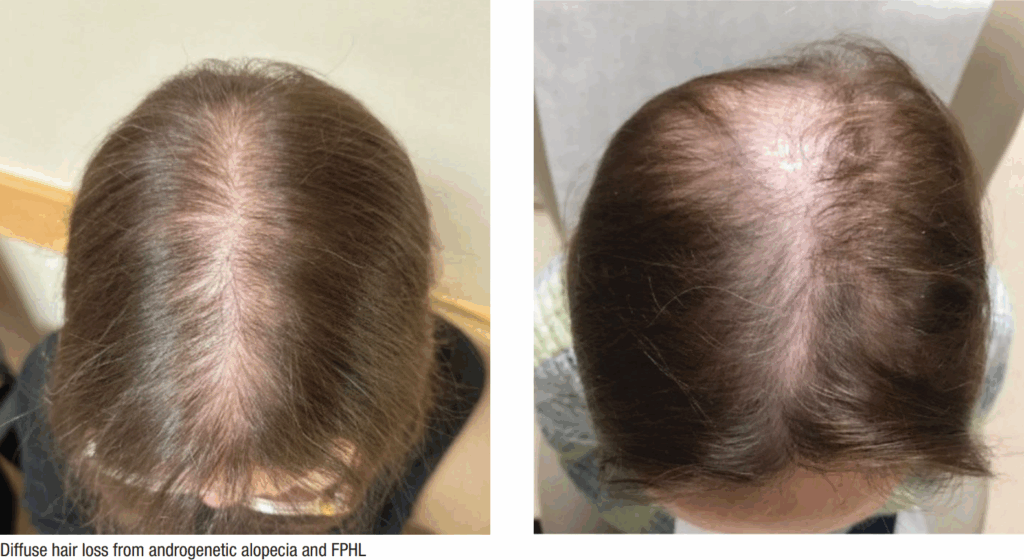

FPHL is the most common type of hair loss seen in women, and the prevalence increases with age; however, it can be a sign of polycystic ovarian syndrome in younger women.3 Gradual follicular miniaturization results in an increased number of vellus (little) hairs in relation to terminal (big) hairs.11 The anagen phase shortens.12 Patients typically describe gradual thinning on the vertex and crown over years. There is notable preservation of the anterior hairline and widening of midline part.12 Thinning and increased scalp visibility rather than shedding is often the predominant patient concern.

TE

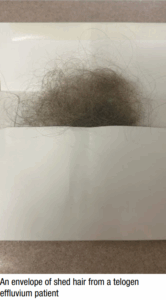

New onset of excessive shedding is the predominant concern of the patient presenting with TE, which results in an abnormal shift of hairs from the anagen phase into the telogen phase, causing the excessive shedding. There may be more than 150-300 telogen hairs shed per day compared to the normal 50-150 hairs.14 There are a number of well-recognized TE triggers (Table 1). There is often a delay of three months from the inciting event to the onset of excessive shedding.13 Reassure patients that most people recover from an episode of TE within 3-6 months.13 TE is usually acute and self-limited. Chronic telogen effluvium is a distinct, much less common subtype of TE and will not be addressed in this article.

| Table 1. Telogen Effluvium Screening Questions |

| In the past 6-12 months, have you experienced any of the following? |

| • Pregnancy, anemia, thyroid disease, menopause, cancer, autoimmune disease |

| • Illness with fever |

| • Hospitalization or surgery |

| • Weight loss > 10 lb |

| • Started a new medication or over-the-counter supplement |

| • Started or stopped a hormone medication such as birth control pill, patch, ring, or IUD |

| • Significant emotional stressor |

| If the answer to any of the above is YES, please elaborate: |

Diffuse AA and Alopecia Areata Incognita

Diffuse alopecia areata (DAA) and alopecia areata incognita (AAI) can pose major diagnostic challenges. Patients often complain of rapid, diffuse hair loss that is not patchy.14-16 Some experts suggest that AAI often develops over weeks, whereas DAA can take longer.14-16 A detailed history, physical exam, trichoscopy, and istopathologic analysis are often required to reach this diagnosis.14-16

Diffuse alopecia areata (DAA) and alopecia areata incognita (AAI) can pose major diagnostic challenges. Patients often complain of rapid, diffuse hair loss that is not patchy.14-16 Some experts suggest that AAI often develops over weeks, whereas DAA can take longer.14-16 A detailed history, physical exam, trichoscopy, and istopathologic analysis are often required to reach this diagnosis.14-16

The Initial Hair Loss Appointment

Managing a hair loss appointment begins with setting clear patient expectations. The objective is to gather comprehensive information, conduct a thorough examination, and provide initial recommendations within a 30-minute time frame. It is important to avoid the pitfall of treating hair loss as a secondary concern during other visits. Encourage patients to schedule a dedicated hair loss appointment to ensure thorough evaluation, diagnosis, education, and discussion of treatment options with realistic expectations for outcomes. Essential tools for the hands-on examination include a comb or cotton-tipped applicator, ruler, dermatoscope, and camera.

A pre-appointment questionnaire can save time by collecting essential information before the visit. These questionnaires can be provided prior to the appointment, in the waiting room, or upon rooming. They help to screen for common conditions like FPHL and TE.

History of Present Illness

Onset of the hair loss should be characterized as acute over weeks/months or gradual over years. Location is identified as diffuse, focal/patchy, or pattern (vertex) on the scalp and whether any body hair is affected. Characteristics are defined as increased scalp visibility vs. bald patches, broken hairs vs. intact bulb, and percentage of ponytail lost. Associated symptoms with hair loss include degree of scalp itch, pain, burning, scaling, and waxy build-up. Any previous treatments attempted will include vitamins, supplements, topicals, shampoos, laser comb or cap, injections, platelet rich plasma (PRP), and prescriptions from online telehealth hair loss-specific companies. Details on application of any topicals and length of treatment can assess if the products were used correctly. Ask the patient if they have taken any treatment advice from other healthcare providers, hairdressers, family members, friends, or social media.

Ask about other possible underlying conditions that can cause diffuse hair loss or can contribute to a patient’s ability to respond to treatment. For example, presence of hirsutism, acne, clitoromegaly, vocal deepening, or irregular menses can be signs of androgen excess or PCOS. Certain autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) can manifest with diffuse hair loss. Asking about the coexistence of arthralgias, rashes, joint stiffness, oral ulcers, and photosensitivity is also recommended. See Table 2 for a list of common systemic conditions that can present with diffuse hair loss. Asking about a current or past history of iron deficiency anemia or vitamin D deficiency is helpful. Timing in relationship to potentially triggering events or medication initiation, discontinuation, or dose adjustment is helpful for individuals with acute onset of shedding, such as in TE. Although any medication can potentially cause hair loss, medications that are commonly implicated in TE are listed in Table 3.

| Table 2. Chronic Diseases Implicated in Diffuse Hair Loss and Initial Screening Tests 22 | |

| Hyperthyroidism/Hypothyroidism | Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) |

| Iron Deficiency/Anemia | Complete blood cell count (CBC), ferritin, iron, transferrin saturation, total iron binding capacity (TIBC) |

| Androgen Excess | Testosterone free/total, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), 17-OH progesterone |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Rheumatoid Arthritis | Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), Rheumatoid factor (RhF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) |

| Intestinal Malabsorption | Vitamin B12, Zinc |

| Table 3. Drugs and Drug Classes Associated with Telogen Effluviuma |

Hormonal

|

Systemic Retinoids or Vitamin A Excess

|

Minoxidil±

|

Anticoagulants

|

Antithyroid

|

Anticonvulsants

|

Interferon-alpha-2b

|

| Heavy metals |

| Beta blockers |

Mood stabilizers, antidepressants:

|

| a adapted from Bolognia 15 * discontinuation of estrogen-containing birth control methods can trigger TE ± typically occurs during the first 4-8 weeks of therapy, self-limited |

Ask about weight loss, especially with the current widespread use of glucagonlike peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists. Gather history on risk for malnutrition and dietary restrictions such as vegetarianism or veganism. Other important questions include:

- Does the patient have an adequate sleep schedule, stress management, or exercise routine?

- Are there any toxicity concerns or history of radiation therapy or heavy metal exposure?

Family history of relatives with thinning hair or autoimmune disease should be noted. Typical style worn and the patient’s hair care routine is informative, as well as whether she has modified it with the hair loss onset.

Clinical Exam

Ideally, the initial exam should be completed on hair and scalp last shampooed 24-48 hours prior to the appointment and free of braids or hair pieces. It should be carried out as follows:

- The patient should sit in a chair that offers access from all sides.

- Observe the overall qualities of the hair and note texture and length.

- Part the hair down the center of the scalp with your comb or cotton-tipped applicator and assess the frontal hairline and midline part.

- Look for short hairs on the anterior hairline indicating new growth, or recession.

- Use a validated scale such as the Sinclair or Ludwig to grade the midline part.

- Observe for broken hairs, patchy areas of loss, or thinned areas.

- Assess the scalp for erythema, scale, pustules, sinus tracts, and presence of follicular ostia or scarring.

- Use the comb to check the entire scalp to see if the findings are consistent throughout.

TIP: Photographing the midline part is helpful to serve as an objective measure and reference point for future visits to monitor progress.

Trichoscopy is a method of hair/scalp image analysis done using any dermatoscope. It will help you see vessels or vascular loops, exclamation hair, variation in hair shaft diameter, halos and dots, orifices of the scalp surface, vellus hair, or tufting. These findings aid in diagnosis and may be diagnostic criteria. Table 4 highlights common trichoscopic characteristics seen in the types of diffuse hair loss addressed in this article. The hair pull is used to confirm abnormal hair shedding. To perform a hair pull, gently pull a group of approximately 60 hairs on the vertex, parietal, and occipital scalp upward with thumb and forefinger. Removal of more than three hairs is considered positive for abnormal hair shed. A tug test assesses fragility of the hair shaft by holding hair near the scalp and tugging from the end. If any breakage occurs, this indicates abnormal hair shaft fragility.

| Table 4. Summary of Key Findings in Various Types of Diffuse Hair Loss11,20,23-27 | ||||

| Historical Cues | Key Physical Exam Findings | Trichoscopic Findings | Histopathologic Findings | |

| FPHL | Gradual onset

Increasing scalp visibility along frontal vertex Shrinking ponytail diameter Hair not growing as long |

Widened midline part

Intact anterior hairline |

Hair shaft diameter variation of >20% hair shaft (early)

Peripilar halos (early Sebaceous gland hypertrophy |

Increased vellous hairs

T:V ratio ≤ 3:1 +miniatruization |

| TE | Sudden onset shedding occurs over months

Usually begins three months after inciting trigger Shedding Clumps of hair Baggy sign See Table 3 for TE medication triggers |

+ hair pull test

+ short hairs along anterior hairline signifying regrowth |

Non-specific

Short non-vellus hair |

Elevated telogen count |

| DAA/AAI | Sudden onset can last weeks or months | + hair pull test

Exclamation point hairs Dystrophic hairs Black dots (cadaverized hairs |

Diffuse empty yellow dots | Histopathologic findings vary with disease stage; can be similar to classic alopecia areata findings

DAA: more likely to have an abundant lymphocytic infiltrate compared to AAI |

Workup and Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory Evaluation

Most dermatology providers agree that some level of laboratory evaluation is recommended for patients presenting with diffuse hair loss. It is reasonable to check thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), vitamin D, iron studies, and complete blood count (CBC) in most patients with diffuse hair loss.17 A thorough history and review of systems (ROS) can determine if further laboratory evaluation is indicated (see Table 2).

Scalp Biopsy

In most cases of diffuse non-scarring hair loss, a thorough history and clinical exam is enough to secure the diagnosis, but sometimes a biopsy is warranted. It remains the standard of care to perform a biopsy if there is any concern for a primary or concurrent scarring alopecia or to confirm the etiology of the hair loss.17 Some patients request a scalp biopsy as they need tangible, concrete evidence to accept their diagnosis. If a biopsy is performed, the most important factor is location. The ideal location is from an area with a positive hair pull exam.18 If the hair pull exam is negative in a non-scarring alopecia patient, a biopsy from the central scalp, typically the vertex, is preferred.11,17-18 This becomes especially important in cases of suspected early female pattern hair loss, in which follicular miniaturization is a key histopathologic clue and the calculation of the terminal hair to vellus hair ratio (T:V ratio) is critical to the diagnosis. A biopsy performed in areas of the scalp other than the vertex such as the occiput or bitemporal regions will result in an inaccurate representation of follicle size.11 When ruling out scarring alopecia, a biopsy from the edge of an active area of inflammation containing some intact hairs is recommended.18

The type of biopsy sampling is also critically important. The gold standard is to perform two 4mm punch biopsies to the depth of fat,11,17-18 one of which is horizontally sectioned (sometimes called “Headington”) and the other of which is vertically sectioned.18-19 Understanding histopathologic sectioning technique is important. Horizontal sectioning allows for accurate assessment and visualization of follicle number and size, telogen count, and calculation of T:V ratio hair ratio.19 This type of sectioning is preferred in non-scarring alopecia.19 Vertical sectioning allows visualization of the entire follicle from root to tip which enables assessment for inflammation and scarring.19 Vertical sectioning is recommended when scarring alopecia is suspected.18-19

If only one specimen can be submitted in a patient with diffuse, non-scarring hair loss, horizontal sectioning is preferred. Many institutions have developed methods and techniques for processing scalp biopsy specimens.19 For example, techniques such as the HoVert allow the dermatopathologist to perform both horizontal and vertical sectioning on a single specimen.20 It is recommended that the clinician consult with their dermatopathology lab to understand which type of processing is available. It is especially important in cases of alopecia that the clinician provide a history and differential diagnosis on the pathology form to assist the pathologist in choosing the proper method of sectioning.19-20

The ability to interpret scalp biopsy results is another area that many clinicians feel inadequately prepared for. A scalp biopsy report will have some key pieces of information that are important for the clinician to familiarize themself with. Firstly, the T:V ratio is derived by assessing the number of terminal hairs compared to vellus hairs in the biopsy specimen. A T:V ratio of 7:1 is considered normal, 4:1 is inconclusive, and anything less than 3:1 is considered diagnostic for female pattern hair loss.11 Second is the telogen count. Normal telogen count varies widely in the literature; however, it is generally accepted that in a normal scalp, the telogen count is approximately 5%-10%.16,21 Conversely, amid an active episode of TE, the telogen count rises to 15%-25% or more.16 DAA will also often have a high telogen count, reversed T:V ratio, and depending on stage of the disease, can demonstrate a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate, which would be absent in TE.15,18 As with any dermatologic disease, clinicopathologic correlation is of utmost importance. (See Table 4 for the common historical, clinical, trichoscopic, and histopathologic findings in the types of diffuse hair loss discussed in this article.)

Conclusion

The evaluation of diffuse hair loss in female patients requires a comprehensive approach that integrates thorough history-taking, meticulous physical examination, and selective diagnostic testing. The psychosocial impact of hair loss, particularly in women, underscores the importance of compassionate care and patient education during consultations. Understanding the nuances of different types of alopecia empowers clinicians to make accurate diagnoses and initiate appropriate treatments. By addressing patient concerns with empathy and utilizing available diagnostic tools effectively, clinicians can improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

REFERENCES

- Androgenetic alopecia. MedlinePlus. Updated July 23, 2023. Accessed June 15, 2024. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/androgenetic-alopecia/#frequency

- Hair growth supplement and treatment market size, share & trends analysis. Grandview Research. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/hair-growth-supplements-treatment-market-report

- Vano-Galvan S. Hair and scalp-related disorders are a trending topic in dermatology, with a significant increase in number of consultations in the last decade. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(1):16-17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10107354/

- Cartwright T, Endean N, Porter A. Illness perceptions, coping and quality of life in patients with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):1034-1039. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19183424/

- Cash TF, Price VH, Savin RC. Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: comparisons with balding men and with female control subjects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(4):568-575. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8408792/

- Ingrassia JP, Buontempo MG, Alhanshali L, et al. The financial burden of alopecia: a survey study. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2023;9(4):e118. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10615414/

- Hwang HW, Ryou S, Jeong JH, et al. The quality of life and psychosocial impact on female pattern hair loss. Ann Dermatol. 2024;36(1):44-52. doi:10.5021/ad.2024.36.1.44

- Aukerman EL, Jafferany M. The psychological consequences of androgenetic alopecia: A systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(1):89-95. doi:10.1111/jocd.14983

- Reid EE, Haley AC, Borovicka JH, et al. Clinical severity does not reliably predict quality of life in women with alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, or androgenic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):e97-e102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3927165/

- Trüeb RM. The difficult hair loss patient: a particular challenge. Int J Trichology. 2013;5(3):110-114. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3927165/

- Blume-Peytavi U, Blumeyer A, Tosti A, et al. S1 guideline for diagnostic evaluation in androgenetic alopecia in men, women, and adolescents. Br J Dermatol. 2011; 164(1):5-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20795997/

- Ramos PM, Miot HA. Female pattern hair loss: a clinical and pathophysiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(4):529-543. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4560543/

- Asghar F, Shamim N, Farooque U, et al. Telogen effluvium: A review of the literature. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8320. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7320655/

- Molina L, Donati A, Valente NS, et al. Alopecia areata incognita. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66(3):513-515. https://www.scielo.br/j/clin/a/BdnvLrrXTtdXHWbNbWc7PND/

- Alessandrini A, Starace M, Bruni F, et al. Alopecia areata incognita and diffuse alopecia areata: clinical, trichoscopic, histopathological, and therapeutic features of a 5-year study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019;9(4):272-277. doi:10.5826/dpc.0904a02. Published correction appears in Dermatol Pract Concept. 2020;10(1)

- Malkud S. Telogen effluvium: a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(9). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4606321/

- Workman K, Piliang M. Approach to the patient with hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(2S):S3-S8. https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(23)00979-9/fulltext

- Pinedo-Moraleda F, Tristán-Martín B, Dradi GG. Alopecias: practical tips for the management of biopsies and main diagnostic clues for general pathologists and dermatopathologists. J Clin Med. 2023;12(15):5004. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37568407/

- Palo S, Biligi DS. Utility of horizontal and vertical sections of scalp biopsies in various forms of primary alopecias. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10(1):95-100. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29403214/

- Nguyen JV, Hudacek K, Whitten JA, et al. The HoVert technique: a novel method for the sectioning of alopecia biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38(5):401-406. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21251040/

- Natarelli N, Gahoonia N, Sivamani RK. Integrative and mechanistic approach to the hair growth cycle and hair loss. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):893. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9917549/

- Kakpovbia E, Ogbechie-Godec OA, Shapiro J, et al. Laboratory testing in telogen effluvium. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20(1):110-111. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33400415/

- Tosti A, Whiting D, Iorizzo M, et al. The role of scalp dermoscopy in the diagnosis of alopecia areata incognita. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(1):64-67. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190962208004039#:~:text=In%20typical%20alopecia%20areata%2C%20dermoscopy,is%20helpful%20in%20the%20diagnosis.

- Sperling L, Sinclair R, El Shabrawi-Caelen L. Chapter 69: Alopecias. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1162-1187.

- Alessandrini A, Bruni F, Piraccini BM, et al. Common causes of hair loss – clinical manifestations, trichoscopy, and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(3):629-640. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33290611/

- Jain N, Doshi B, Khopkar U. Trichoscopy in alopecias: diagnosis simplified. Int J Trichology. 2013;5(4):170-178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/

PMC3999645/

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Veronica Richardson, MSN, CRNP, ANP-BC, DCNP is a Dermatology Nurse Practitioner at Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System in Philadelphia, PA.

Rachel Woods, FNP-BC, DCNP, is a Dermatology Nurse Practitioner at Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Health System in Philadelphia, PA.

DISCLOSURES

None