Susan Hopkins, BA, MB, BCh, BAO, MSc, FRCPI, FRCP, with Bob Kronemyer

COVID-19 reinfections are rare, according to the SARS-CoV-2 Immunity & Reinfection Evaluation (SIREN) study, a large, prospective cohort trial of staff working in the publicly funded hospitals of the National Health Service

(NHS) across the United Kingdom.1

As principal investigator of the study, I feel there is an urgent need to better understand whether individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 are protected from future SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Study methods and findings

At enrollment, beginning June 18, 2020, participants were assigned to either the positive cohort (antibody-positive or prior polymerase chain reaction (PCR)/antibody test positive) (n = 6,614) or the negative cohort (antibodynegative, not previously known to be PCR/antibody positive) (n = 14,173). Study participants underwent regular SARS CoV-2 PCR and antibody testing every 2 to 4 weeks, and completed questionnaires on symptoms and exposures every 2 weeks.

Potential reinfections were clinically reviewed and classified according to case definitions: confirmed, probable, and possible (subdivided by symptom status), depending on hierarchy of evidence.

Individuals with primary infection were excluded from analysis if the infection was confirmed by antibody only.

Reinfection rates in the positive cohort were compared against new PCR positives in the negative cohort using a mixed effective multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Between June 18, 2020, and November 9, 2020, 44 reinfections (2 probable, 42 possible) were detected in the baseline positive cohort, representing 1,339,078 days of follow-up. This compares with 318 new PCR-positive

infections and 94 antibody seroconversions in the negative cohort, comprising 1,868,646 days of follow-up.

PCR positivity in the positive cohort peaked in the first week of April 2020 and for the negative cohort the last week of October 2020. By November 24, 2020, there were 409 new infections detected in the negative cohort, of

which 318 were new PCR-positive infections. Among these new PCR-positive infections, 79% were symptomatic at infection, with 62% having typical COVID-19 symptoms and 17% with other symptoms. In addition, 12% were

asymptomatic and 9% did not complete a questionnaire at the time of their symptoms.

The cumulative incidence of probable, symptomatic possible, and all reinfections in the positive cohort between June 2020 and November 2020 was 0.3, 2.3, and 6.7 per 1000 participants, respectively, whereas the incidence of symptomatic and all new PCR infections in the negative cohort was 17.6 and 22.4 per 1000 participants, respectively.

The incidence density per 100,000 person-days between June 2020 and November 2020 was 3.3 reinfections in the positive cohort vs 22.4 new PCR-confirmed infections in the negative cohort.

The adjusted odds ratio was 0.17 for all reinfections (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.13 to 0.24) compared to PCR-confirmed primary infections.

The median interval between primary infection and reinfection was in excess of 160 days. A prior history of SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with an 83% lower risk of infection, with median protective effect observed 5 months following primary infection. This is the minimum likely effect because seroconversions were not included.

The SIREN study also contains preliminary evidence that, following infection, naturally “protected” individuals may still acquire and then carry high levels of virus in their mouths and throats and serve as vectors for infecting

susceptible people. However, findings of the study might not pertain to newer, emerging COVID-19 variants.

Answering important questions

The SIREN study seeks answers to the most important questions about reinfection and COVID-19. My blog (https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2021/03/11/the-sirenstudy-answering-the-big-questions/) addresses

how Public Health England (PHE), where I am a healthcare epidemiologist consultant in infectious diseases and microbiology, has led the national effort to develop the science that helps decision-makers control the disease.

Since the outset of the pandemic, interest in antibodies and antibody testing has grown immensely. Antibodies are part of the human body’s immune response to an infection. They are a special protein that seeks, finds, and

attaches itself to an unwelcome invader, such as COVID-19. After the immune system has flushed out a cold, cough, or COVID-19, these antibodies do not disappear.

Testing for the presence of COVID-19 antibodies can tell us if someone has had the virus before and advance our understanding of the spread of the virus. The more we understand about antibodies—and the more we know about

COVID-19 reinfection in general—the more information we have at our disposal to help decision-makers control the spread of the disease.

The current study emerged from smaller studies surveying PCR positivity and antibody positivity in healthcare workers, which demonstrated variable prevalence of acute infection (from 0.5% to 3% across hospitals) and high seroprevalence (prior infection) in healthcare workers.

The nationwide effort of the present study is reflected by 131 NHS trust sites up and running with a cohort of 49,282 volunteers by early March 2021. The public-spiritedness of those who consented to participate among

the 4 United Kingdom nations has helped PHE scientists to answer the big questions about this virus.

This has been no mean feat. PHE’s data gathering, data management, and database building have been critical in ensuring that the right information flows to the right place at the right time.

Measuring vaccine effectiveness

As the rollout of vaccines began, the study rapidly updated to include information about whether participants had been vaccinated. By expanding the protocol of the study to include vaccine information, SIREN has been able to

assess the effectiveness of vaccines.

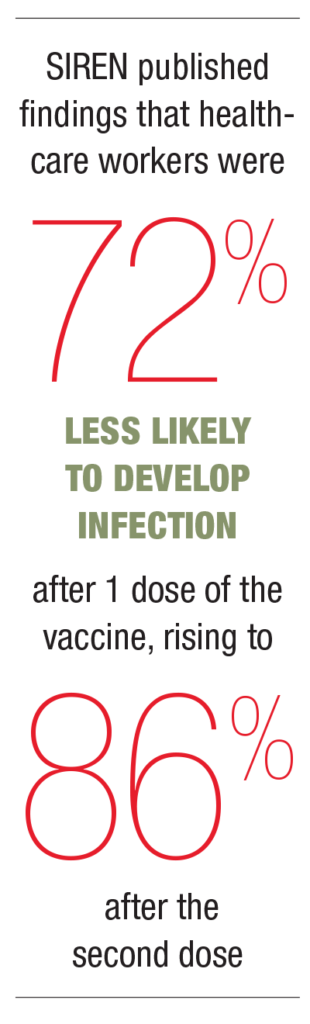

In February 2021, SIREN published findings that healthcare workers were 72% less likely to develop infection after 1 dose of the vaccine, rising to 86% after the second dose.

SIREN concluded that the vaccine’s protection starts after 2 weeks, and that this protection also helps to reduce the spread of infection. If an individual is not infected, he or she cannot spread the virus; the more individuals who cannot spread the virus, the greater protection for the whole population.

By showing evidence that COVID-19 vaccines are effective, the SIREN study has also provided an answer to the question of whether the vaccination program will help end lockdown restrictions. The answer is—in parallel with

other measures, including maintaining hand hygiene, using face coverings, and observing social distancing—a cautious, careful, but optimistic “yes.”

Since its inception, the SIREN study has answered the most important questions about COVID-19 infection, reinfection, and antibodies.

REFERENCES

- Hall V, Foulkes S, Charlett A, et al. Do antibody positive healthcare workers have lower SARS-CoV-2 infection rates than antibody negative healthcare workers? Large multi-centre prospective cohort study (the SIREN study), England: June to November 2020. MedRxiv (the preprint server for health sciences). doi:org/10.1101/2021.01.13.21249642